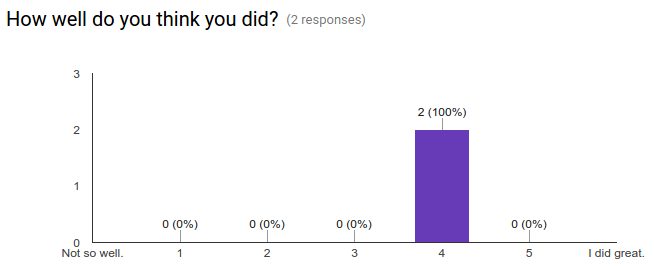

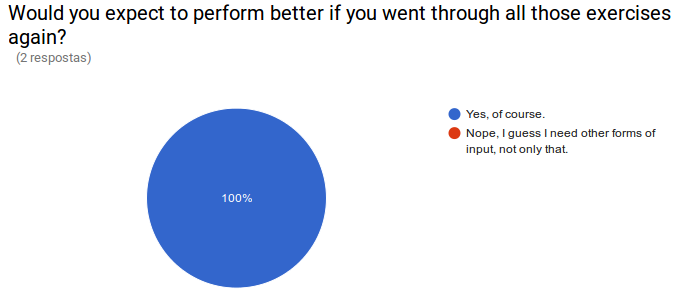

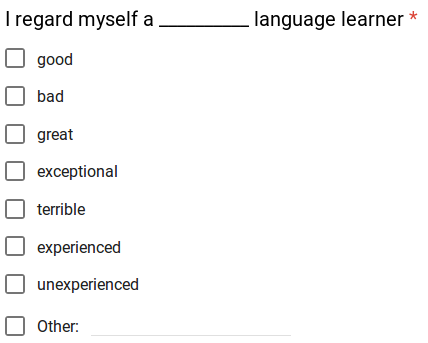

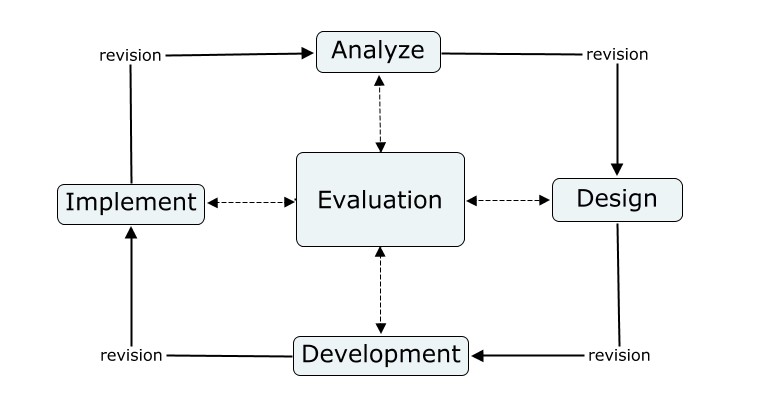

It is a recommended practice to conduct a formative evaluation during all stages of instructional design, according to the ADDIE model framework (Smith; Ragan, 2005). In light of that, I have created a customized, open-access, website that stores and displays all information related to this thesis project.

Such website became at the same time my central workplace and a channel to showcase my progress. It has offered my community of collaborators (my peers, instructors, and committee members) an ongoing and unlimited opportunity to access and review my work during the whole design process.

Image 4 - Visual representation of the ADDIE Model

In this section, I describe the main functions, features, and mechanisms of this website. In addition to that, I explain and illustrate how creating and using this website has impacted my design decisions at different times and stages.

Git, Jekyll, GitHub Pages

Facing the need to have a simple, easy, and fast way to communicate with my community of collaborators, I began to search for software and tools that could be helpful. What I first realized was that I needed some versioning control to document my process. This was particularly important because, besides working on an extensive design document, I would also program my entire software prototype.

“What is “version control”, and why should you care? Version control is a system that records changes to a file or set of files over time so that you can recall specific versions later”. (Chacon; Straub, 2014) Through research, I confirmed that Git was a suitable tool for my needs:

“Git is a free and open source distributed version control system designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with speed and efficiency” (Git, n.d.)

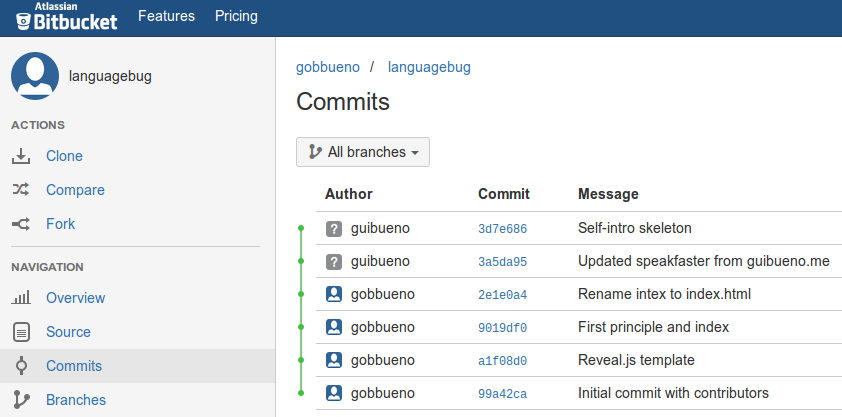

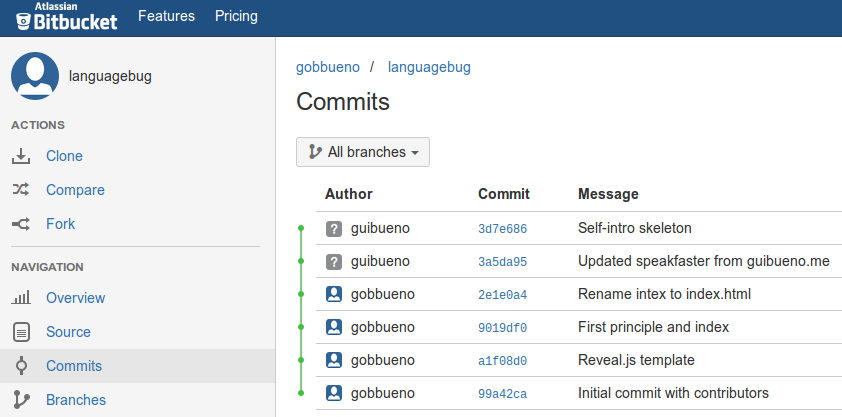

My first attempt was to create a private repository on BitBucket (a repository platform that runs Git). Some of my committee members, who are particularly proficient in technology and know how to operate Git, were added as contributors to that repository, so that:

- they would be able to see, comment, and change any file at any time,

- while I would be able to keep track of those changes and comments.

Image 5 - Initial project repository on BitBucket

However, after only one week, I realized that repository was not generating any engagement between my committee members and I. This made me realize that using BitBucket and interacting with only the committee member who could operate Git would not be enough for a valid, continuous evaluation. Therefore, I kept looking for alternatives and found out about Jekyll and GitHub Pages:

“Jekyll: A tool for creating static HTML websites from a set of templates and data. Jekyll is used by GitHub to create static web pages for GitHub hosted projects”. (Wagstrom; Jergensen, 2012, p. 5)

I consulted with my I.T. specialist committee members Daniel Negri and Ludmilla Aires, who both agreed this tool would suit my needs.

For about two weeks, I focused all my effort to learn how to install, operate and build a thesis project website using those tools. This experience fulfilled a set of goals I have had since the beginning of the thesis course:

- to learn to operate version control systems,

- to re-connect with coding, especially for the web, and

- to give the access to my design process and products to anyone.

This process is further described on Blog#7 New Thesis Website.

Centralization

As I realized the potentials of GitHub Pages combined with Jekyll, I began to design my website to be the central workplace and project management tool for my thesis. Here I briefly describe the functions and sections I have created and how they have helped me structure, organize, and collect feedback on my process.

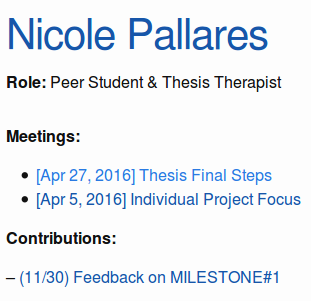

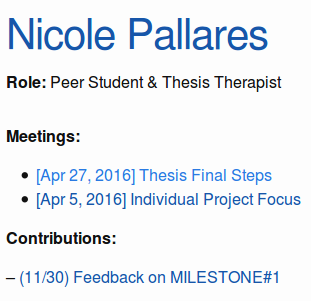

Me

This section was designed to provide my basic biographic information, plus the list of committee members, their roles and contributions to the project. For example, by accessing the page titled Nicole Pallares, it is possible to see the written feedback provided by this committee member and an informal log of the meetings we have had.

Image 6 - Example of a committee member’s page

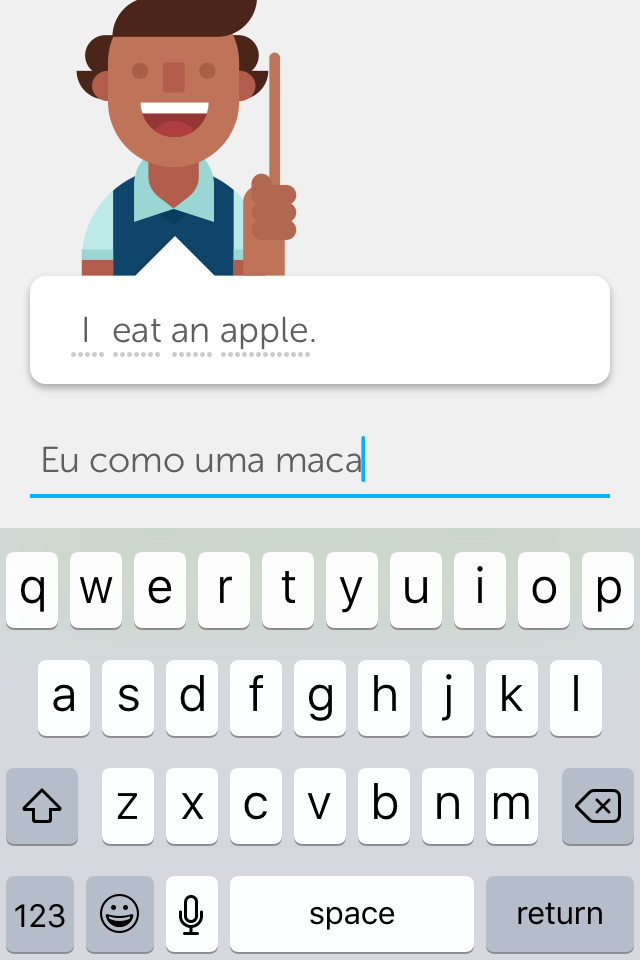

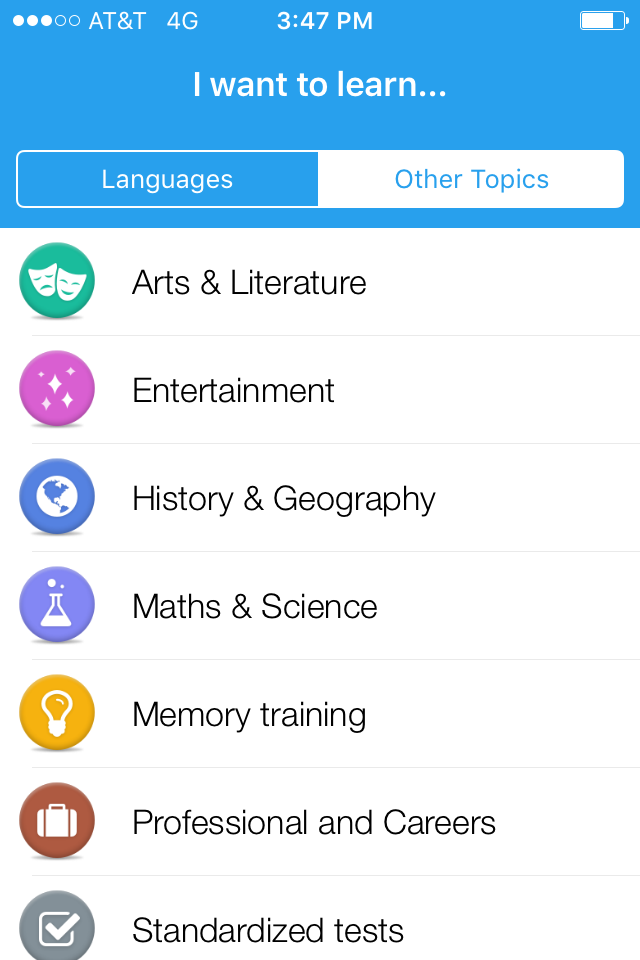

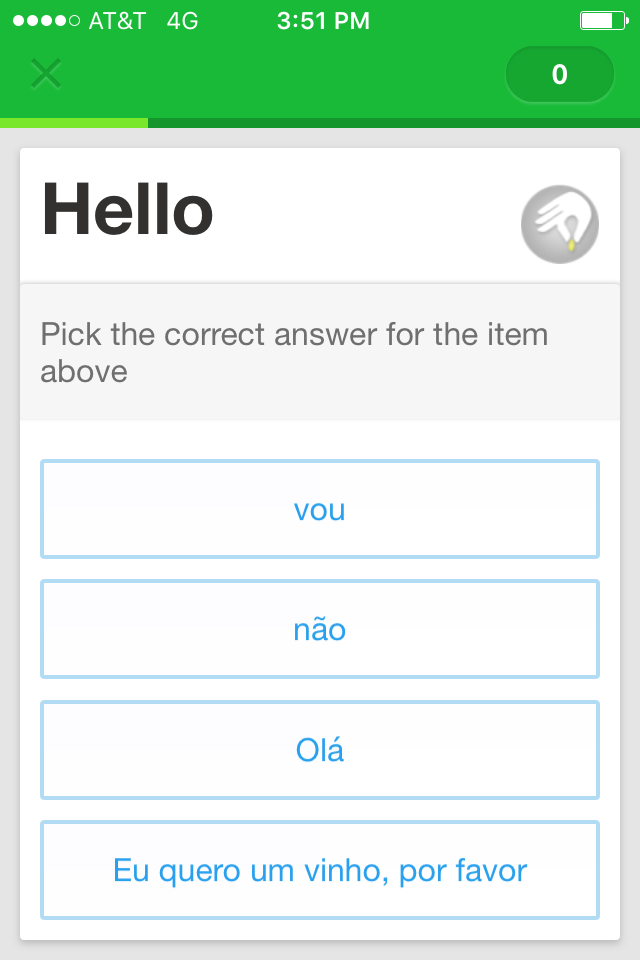

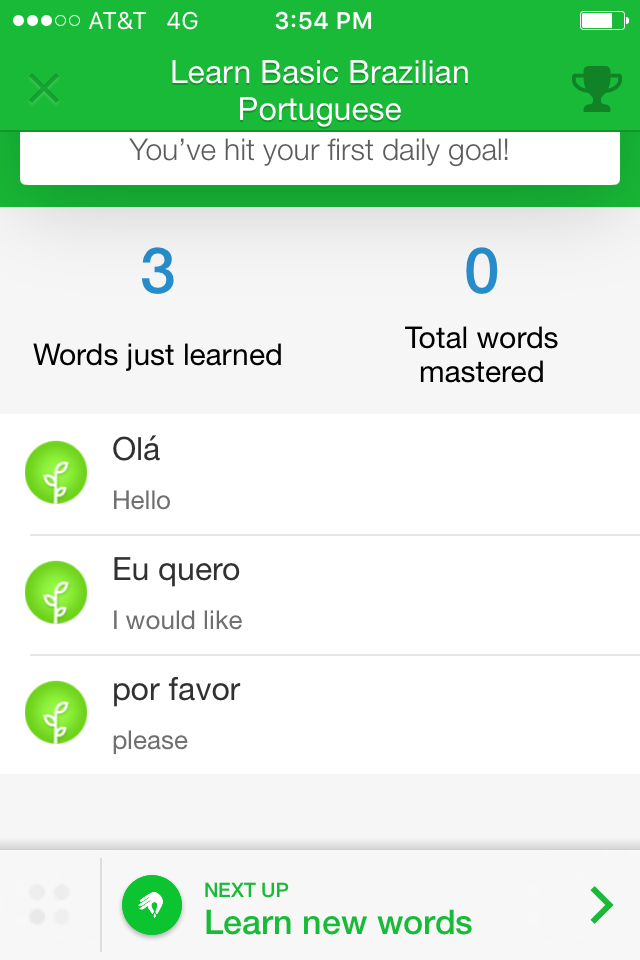

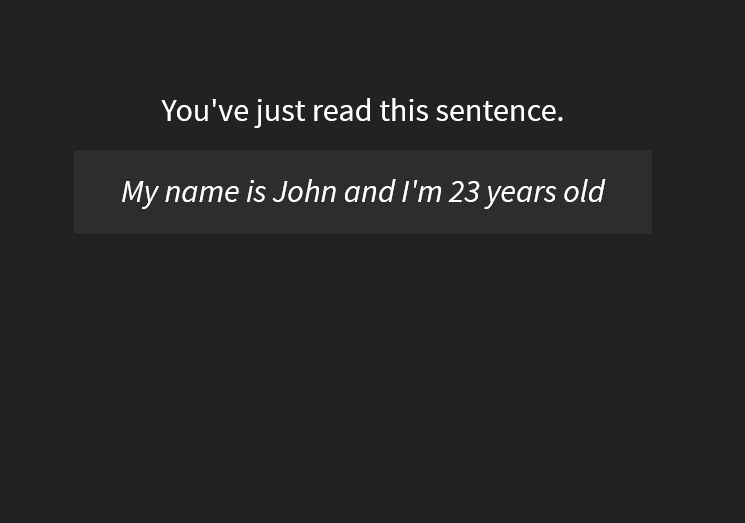

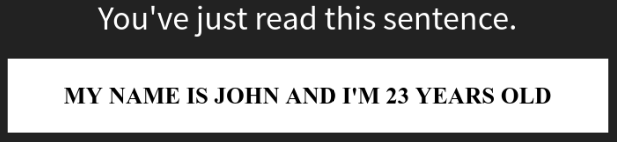

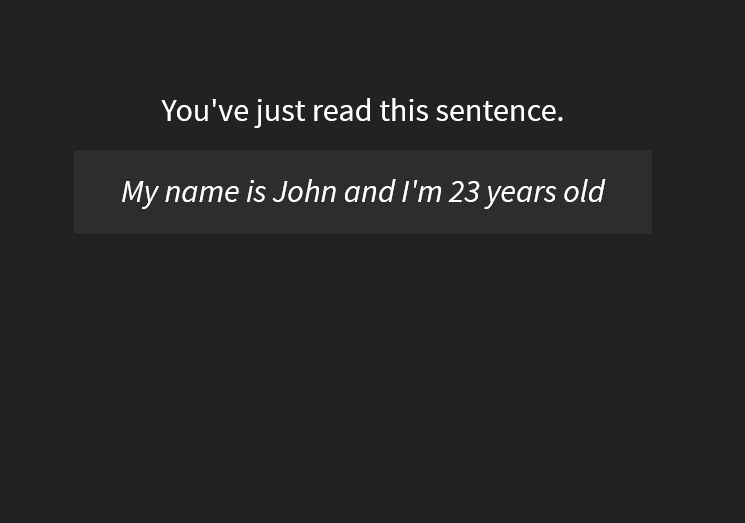

Demo

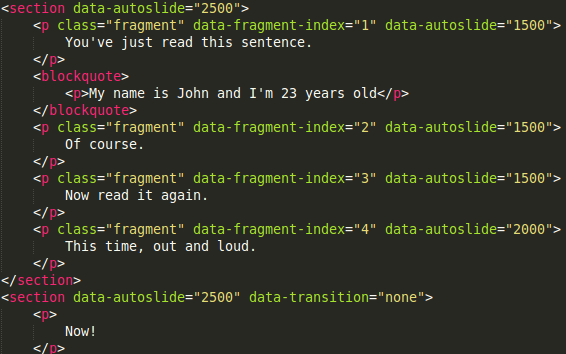

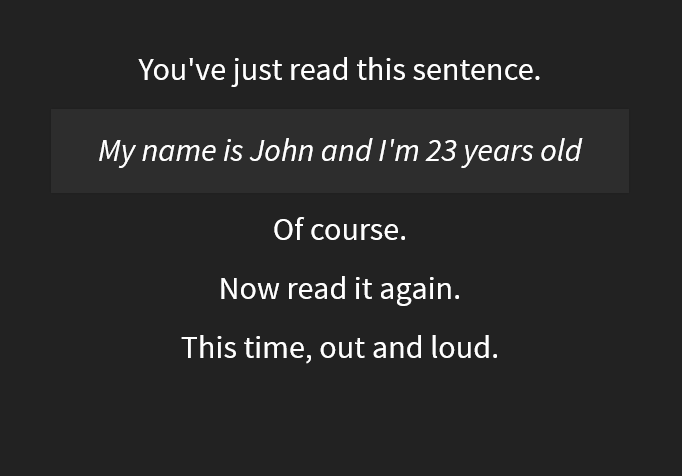

The “Demo” section displays the responsive prototypes I have created. While the final thesis paper (or design document) needs to be static, this website allows users to interact with my design iterations created on MockingBot or using Reveal.js.

Image 7 - Reveal.js prototype

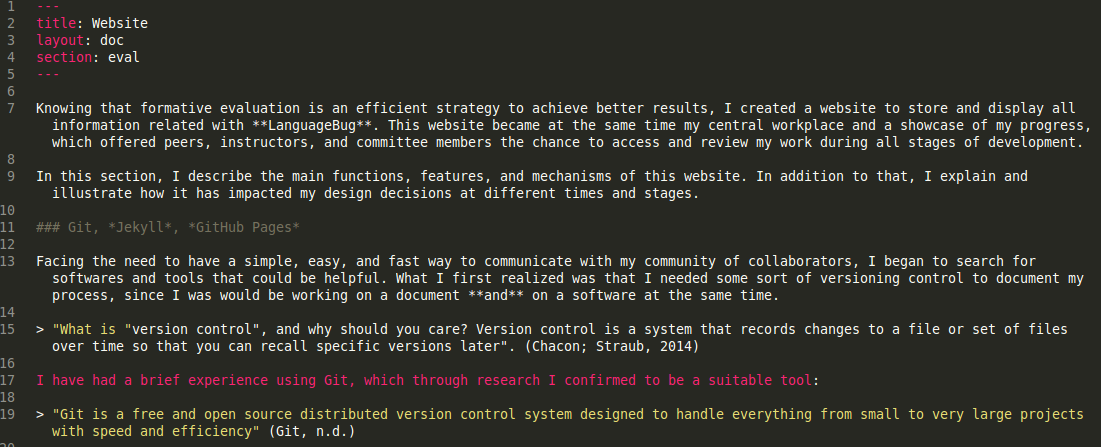

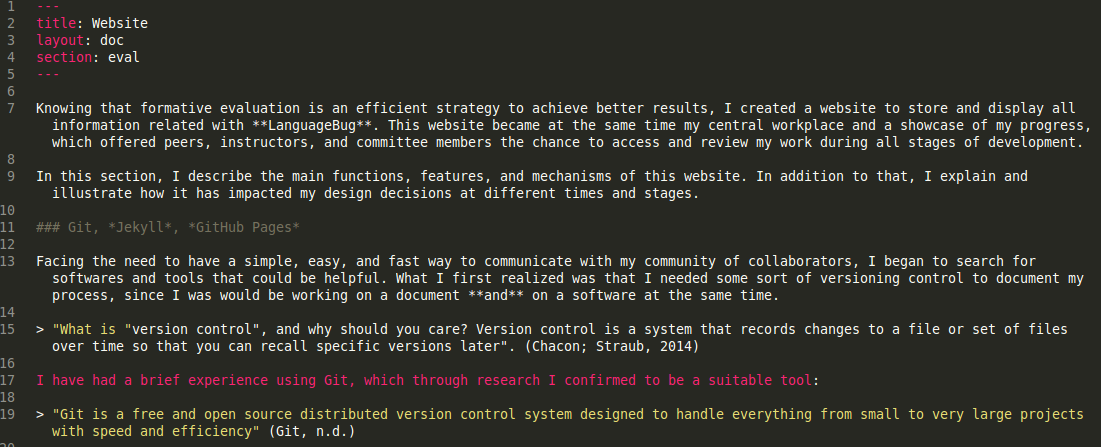

Doc

By accessing the “Doc” page, users can see all sections of the design document, that is, of the final thesis paper. Each section comes from an individual local file and produces a particular permalink.

Image 8 - Screen-shot to show how document writing was done

This enabled me to work separately on each section, which has simplified and increased my workflow. Getting feedback from my community of collaborators also became easier. For example, if I have been devoting time to the Landscape Audit section, I can send a simple URL link to my community of collaborators, and they will directly access the Landscape Audit page on any device.

Logs

The “Logs” section was designed for accountability and management purposes. First, it provides a general landscape of my work:

- my current goals,

- a list of tasks and achievements

- the scheduled events

- my role in the next class meeting.

All this information is stored on a weekly basis, providing longitudinal information of my process. Through these logs, my committee members and I can determine how well I am splitting my work time/energy.

This section also stores brief reports from all meetings. It prevents me from forgetting or losing valuable hints, notes, pictures, and sketches produced during these formal or informal encounters.

Finally, the “Logs” section contains the most important upcoming deadlines and an entire Blog (or Reflection Journal) on which I freely discuss my design process, feelings, achievements, and uncertainties.

Networked Software Development Ecosystem

Since this website is hosted on GitHub Pages, all my thesis project files, including these very words, are open for anyone to contribute to, access, modify, re-use, or share.

In other words, LanguageBug qualifies as a Free / Open Source Software (F/OSS). The underlying ideologies of F/OSS (Stallman, 2002; Coleman, 2013), open licensing (Lessig, 2004) and Open Educational Resources (OER) (Atkins; Brown; Hammond, 2007) have, indeed, guided my thinking about this project from the beginning.

Wagstrom and Jergensen (2012) call this architecture of development “social coding”. The authors state that tools such as GitHub are “changing the way open source is perceived and how it is practiced” (p. 1)

Being open to social coding is a merely good start, which does not guarantee the participation of other individuals on the development of LanguageBug. But doing make me understand better the mechanisms of F/OSS, which will eventually help me escalate to an actual social coding practice. In fact,

“there is still much to learn about the roles that individuals play in open source development and how we can best ensure that these projects are successful and that individuals get the support they need to continue to grow” (Wagstrom; Jergensen, 2012, p. 11)

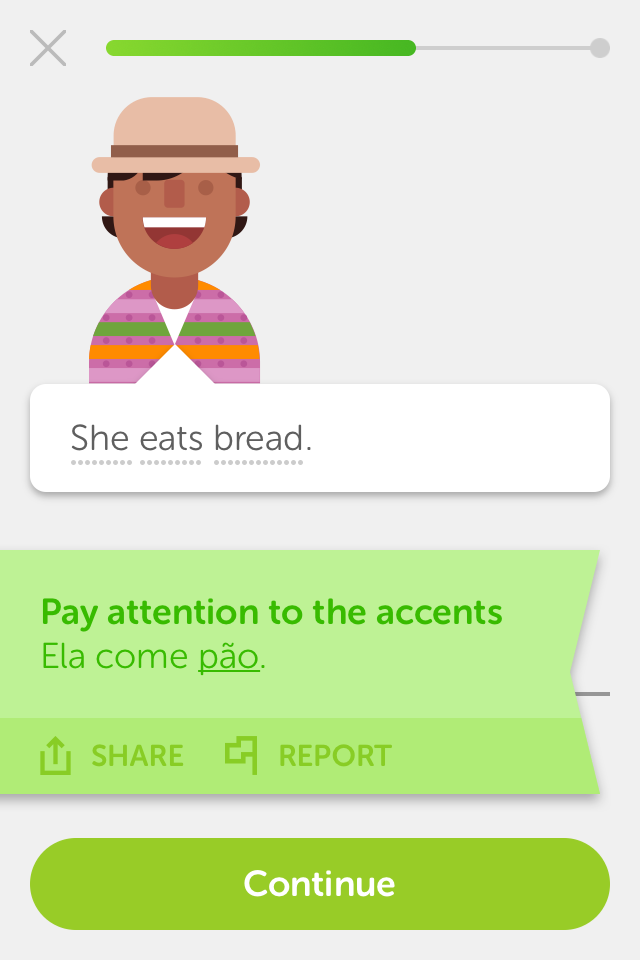

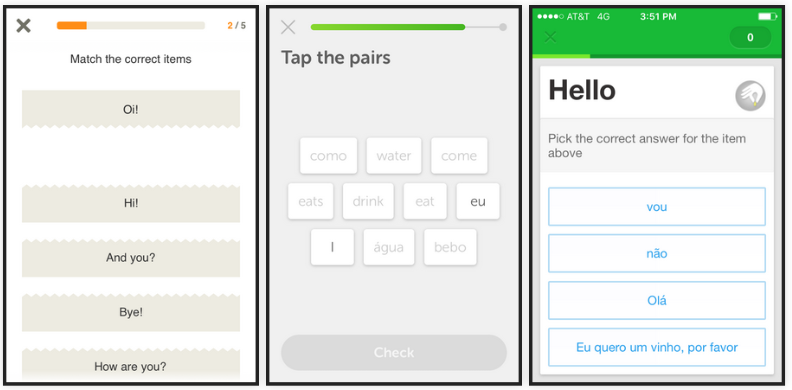

Getting Feedback

At different occasions, the feedback I have received from my community of collaborators was crucial to the improvement of my designs. Most of this communication has happened through either private message channels (email, Facebook, and SMS messages) or on my Slack channel, to which all my peers had access.

Image 9 - Post of initial storyboard on my channel on Slack

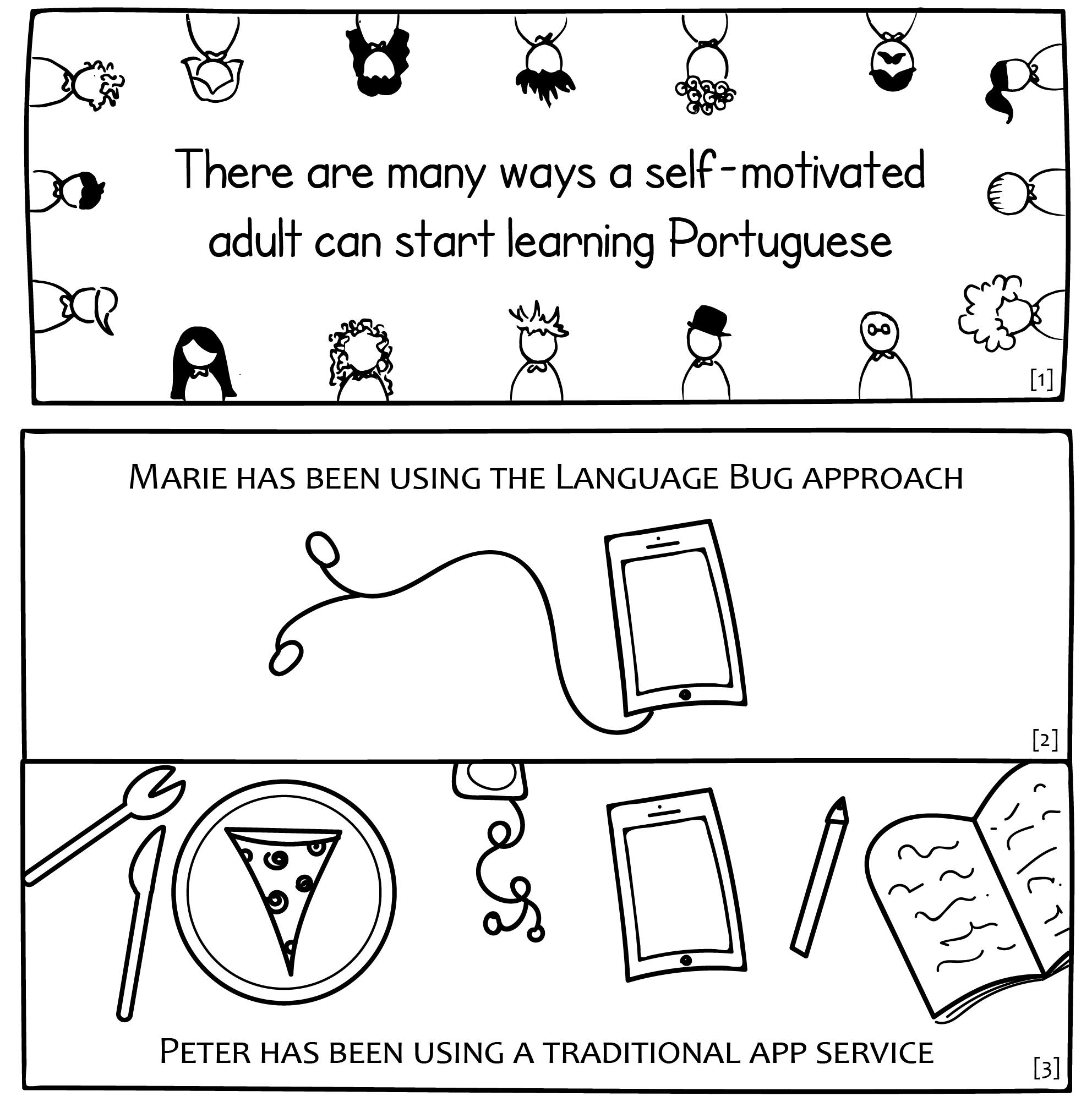

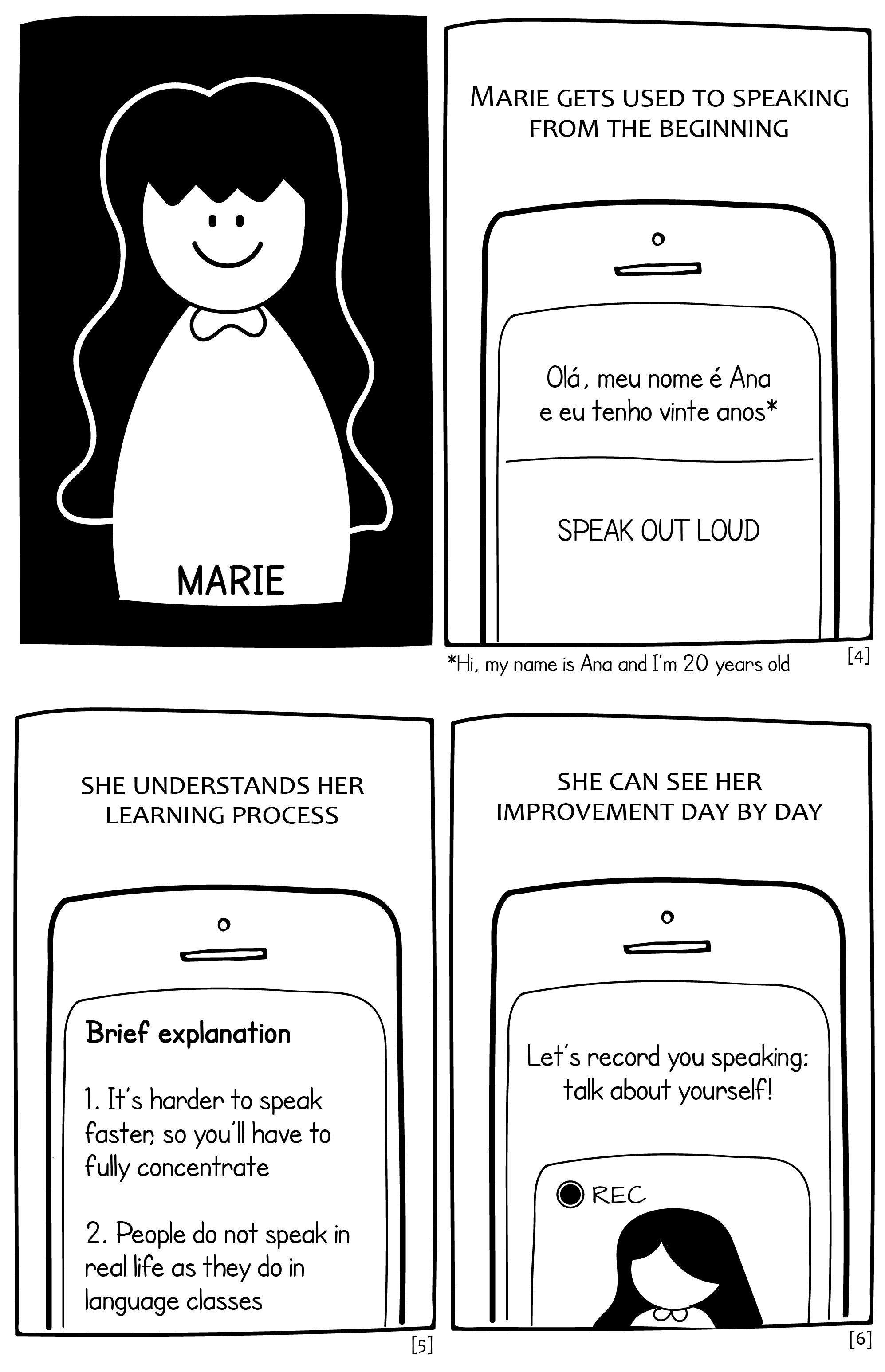

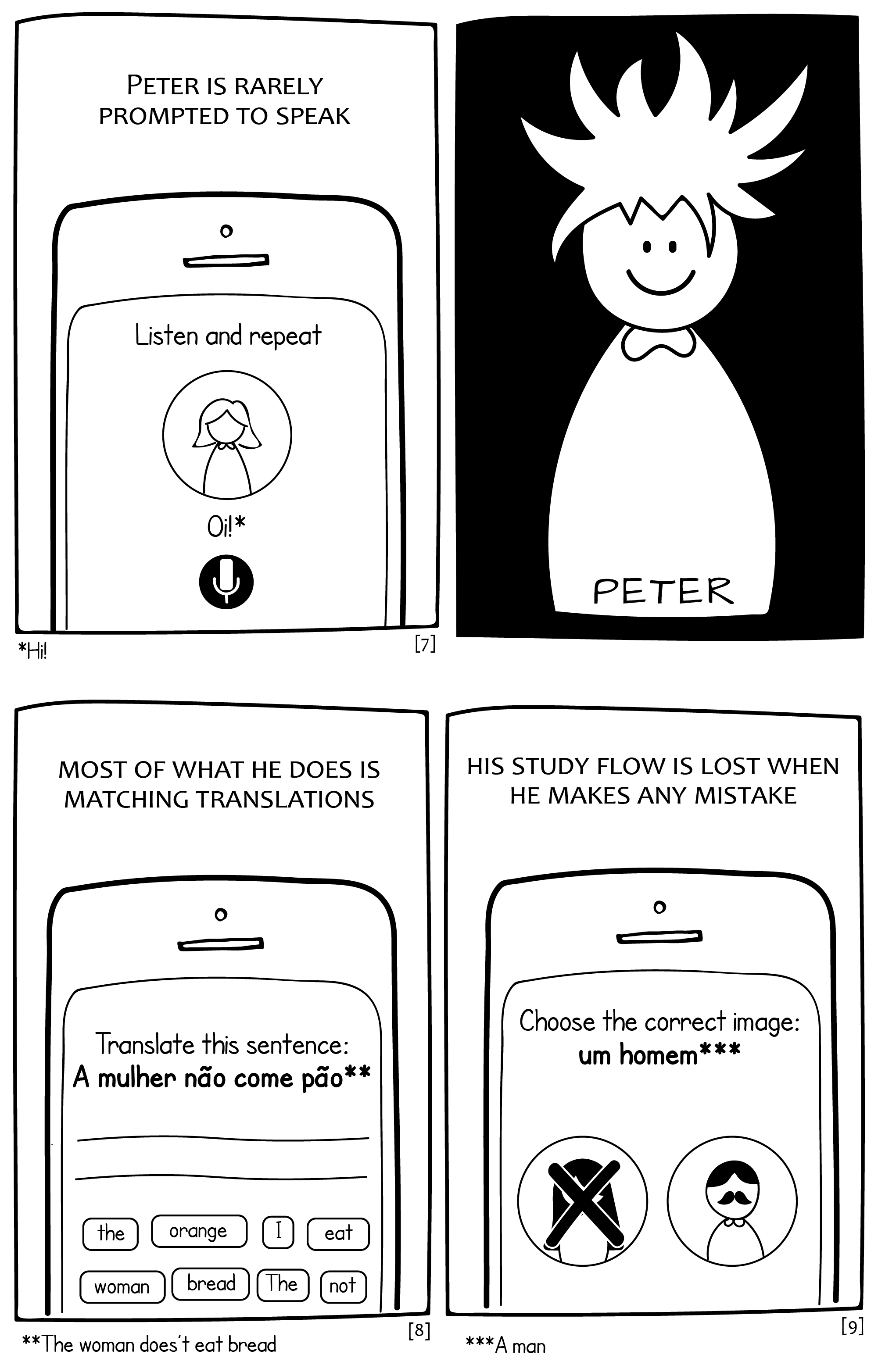

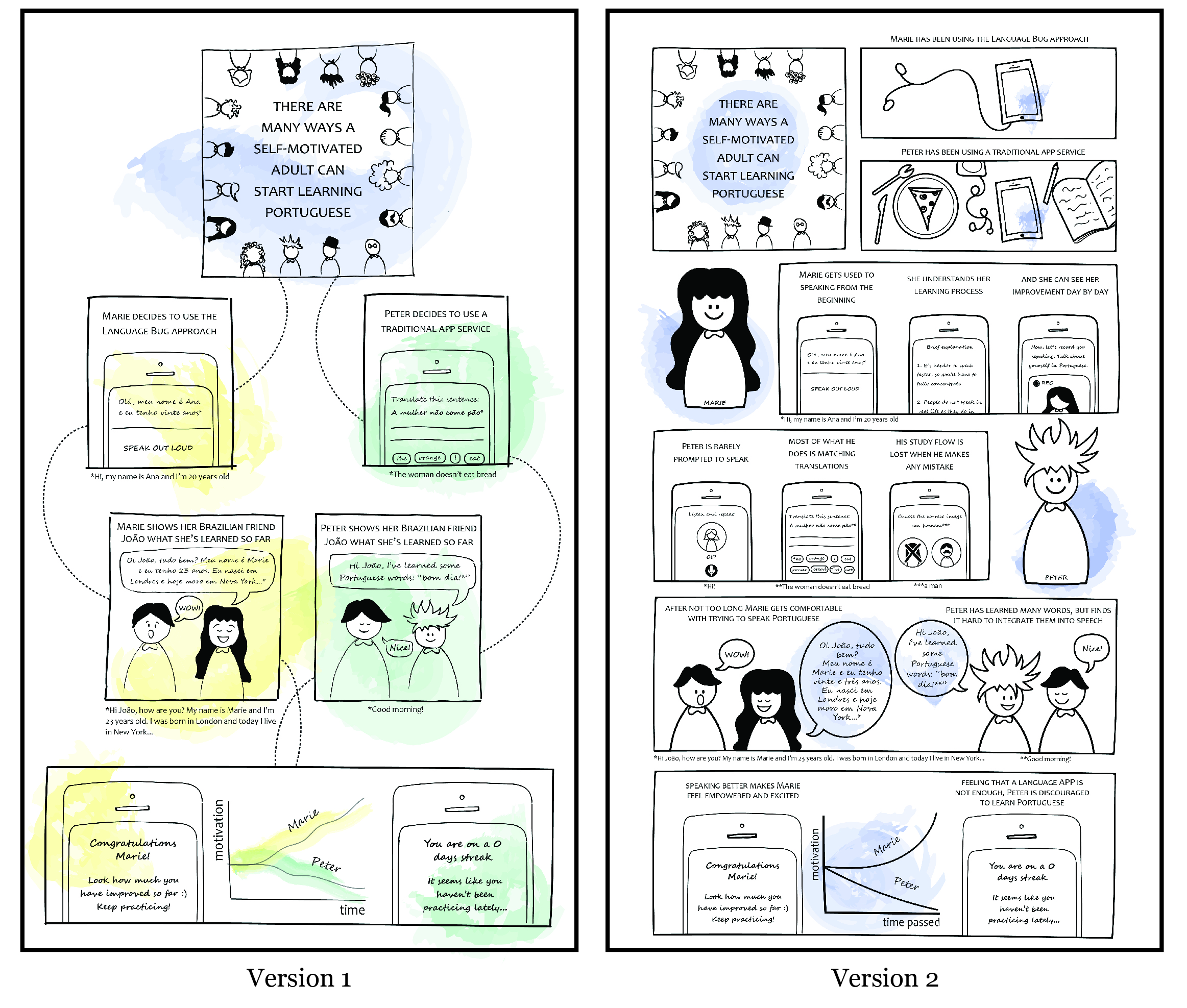

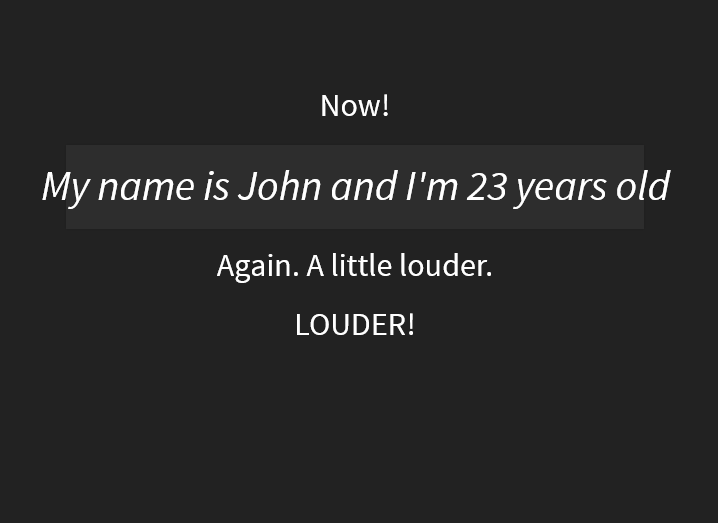

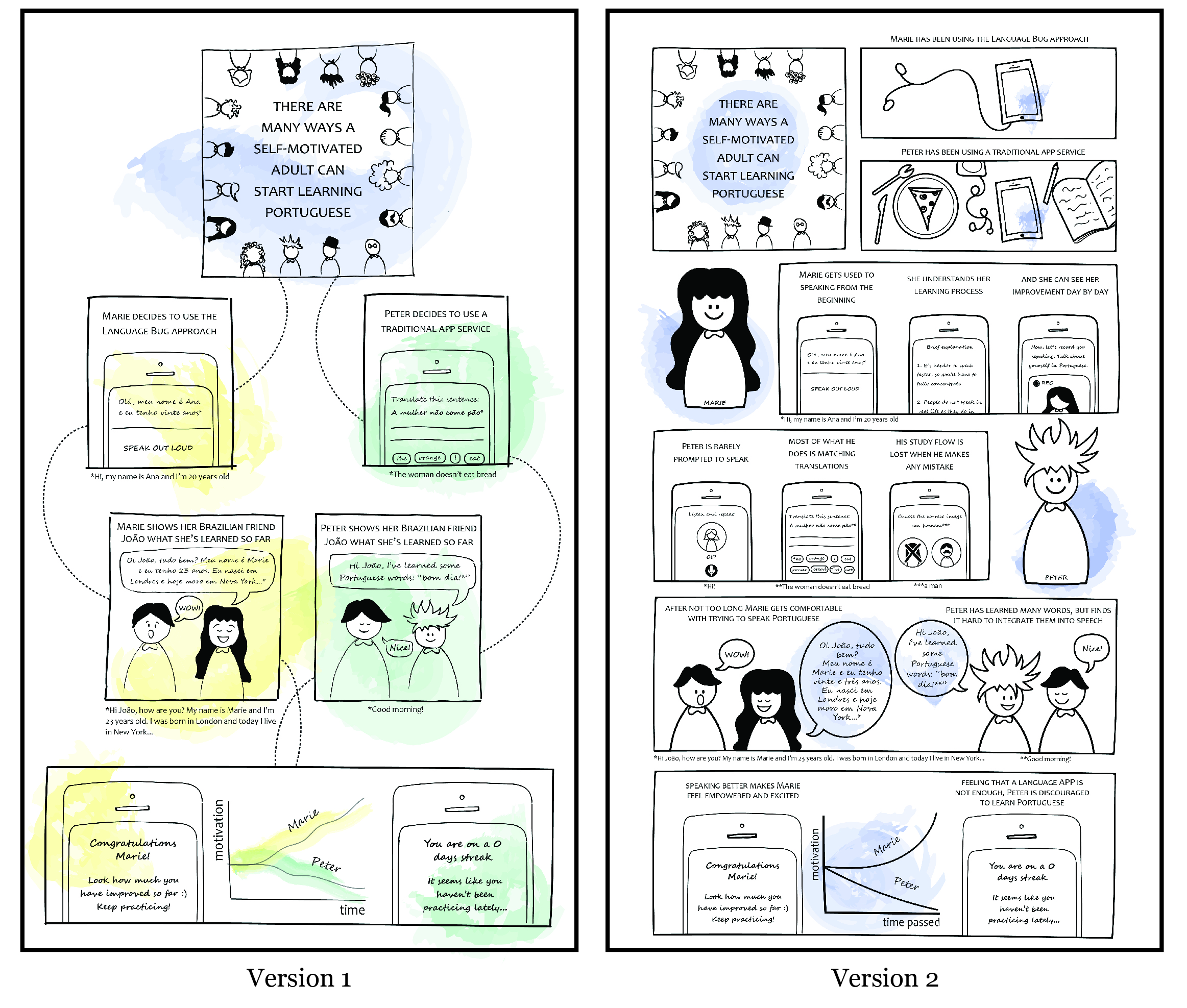

For example, when I shared my first draft of a Storyboard, I received a lot of attention from my peers (five people have commented on it in less than 24 hours). They seemed to agree that the storyboard was visually appealing, but did not describe well my solution and context:

hani: Your storyboard looks great Gui! It completely describes the potential advantages your app has as opposed to traditional methods in language learning for self-motivated learners. I am just wondering if maybe one or two more boxes to elaborate more why these differences exist to compare to other apps. I also love the way you develop your landscape audit!

nicole: it feels a bit more like a comparison than a storyboard. Still super nice actually but if you add a bit more detail into what actually happens inside (yours) and inside (other app) you would have two storyboards that compare which is actually pretty awesome.

These suggestions and comments were taken into account when building the new version of the storyboard (with the help of my talented committee member, Amanda Letícia). As it can be easily seen on this image, the amount of information to describe how both LanguageBug and most of the other applications operate has increased significantly.

Image 10 - How my storyboard has changed after formative evaluation

Conclusion: work-in-progress draft

The formative evaluation of the design of LanguageBug was accomplished by using Git, GitHub Pages, and by sharing each individual step of my design process with my peers and friends. I have obtained valuable information and suggestions from experienced designers which different expertise.

As a side effect, such an intense flow of suggestions and ideas has made me get used to treating all pieces of my project as work-in-progress drafts.

Although constantly lacking a sense of completion could be a problem for a final academic project, I consider this a positive side-effect. It has helped me understand I have “permission to explore” and even to fail, which aligned me with the Embrace Ambiguity design mindset (IDEO.org, n.d.).